Basic guide to ERCP in patients with reconstruction of the intestine after pancreaticoduodenectomy

Naoki Okano, MD, PhD

Toho University Omori Medical Center

Operation environment

・Equipment used (Fig. 1 on Page 1)

As it takes longer to administer therapeutic pancreaticobiliary endoscopy to a postoperative intestine than it does to perform ordinary ERCP; carbon dioxide (CO2) gas is used for insufflation.

Because CO2 gas has excellent bioabsorbability, excessive stretching of intestine can be avoided, and small bowel can be effectively shortened.

The procedure is performed while monitoring patient with electrocardiogram (ECG), pulse oximeter, and continuous sphygmomanometer. This makes it possible to understand the patient’s intraprocedural respiratory circulatory kinetics.

Use of a distal attachment helps reduce occurrence of so-called “red ball” phenomenon in which the endoscope tip comes in contact with mucosa. For this reason, use of a distal attachment makes it easier to discern the direction of lumen.

・Sedation method

As in ordinary ERCP, this procedure is performed under

conscious sedation. Midazolam, diazepam, flunitrazepam, or

propofol is used as a sedative and pethidine or pentazocine as

an analgesic. In addition, hyoscine butylbromide or timepidium

bromide is used as an anticholinergic in order to suppress

intestinal peristalsis. If an anticholinergic cannot be used,

glucagon is used as appropriate.

・Patient position

Standard patient position is prone position. This prevents

aspiration, as well as allowing you to better assess the shape

of the endoscope insertion tube under fluoroscopy. When hand

pressure is necessary, switch to the semi-prone position.

Basic operation of sSBE system

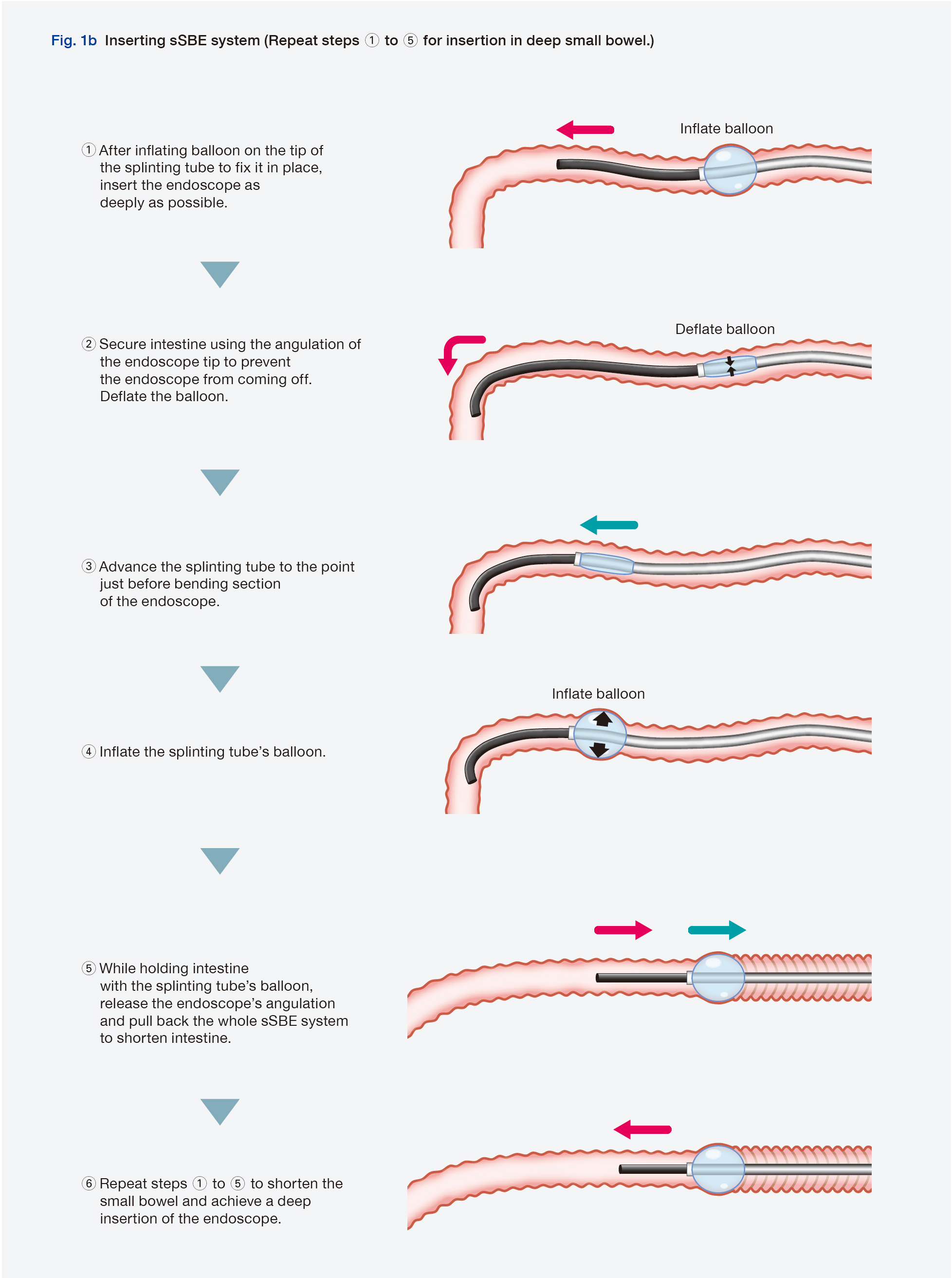

The short-type single balloon enteroscopy (sSBE) system is a combination of SIF-H290S small intestinal videoscope and ST-SB1S splinting tube with a built-in balloon on its tip (Fig. 1a).

First of all, insert the endoscope into small bowel. After inflating the balloon of the splinting tube, further advance the endoscope as much as possible (Fig. 1b,1). Secure intestine using the endoscope tip’s up/down and left/right angulation (Fig. 1b,2).

Next, advance the splinting tube with the balloon deflated (Fig.1b, 3), and when the tip of the splinting tube reaches a point just before the bending section near the distal end of the endoscope, inflate the balloon (Fig. 1b, 4). When advancing the splinting tube, do so while confirming the position of the distal end of the splinting tube with fluoroscopy to ensure it stays in place. Once the balloon has been inflated, release the angulation and then pull back the endoscope and splinting tube to shorten the intestine (Fig. 1b, 5). Repeat this maneuver to fold the small bowel toward the proximal side. This will shorten it and allow you to successfully insert the endoscope into the deep small bowel (Fig. 1b, 6).

When inserting the splinting tube, pull the endoscope slightly so it will not get pushed in. If you feel any resistance while inserting the splinting tube, take extra care as there is a chance that mucosa could get caught between the splinting tube and endoscope. If this happens, jiggle the endoscope or splinting tube to reduce the chance of catching the mucosa. When shortening intestine, pull the endoscope and splinting tube slowly. If you feel any resistance, do not use force. Instead, attempt shortening in combination with fluoroscopy as appropriate.

If the endoscope is significantly twisted or deep insertion is difficult because the endoscope tip has bent into a shape like a walking stick handle, have an assistant perform hand pressure as appropriate to facilitate insertion.

Insertion techniques

・ Anatomy

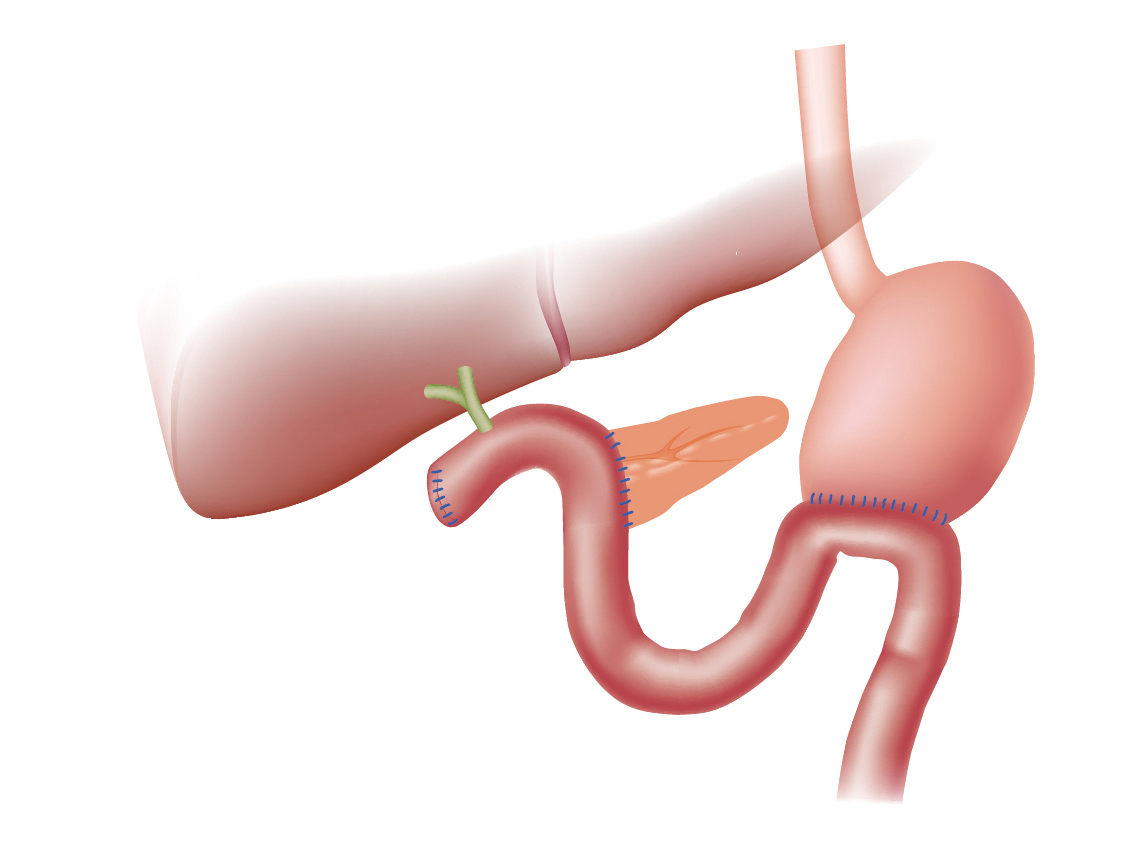

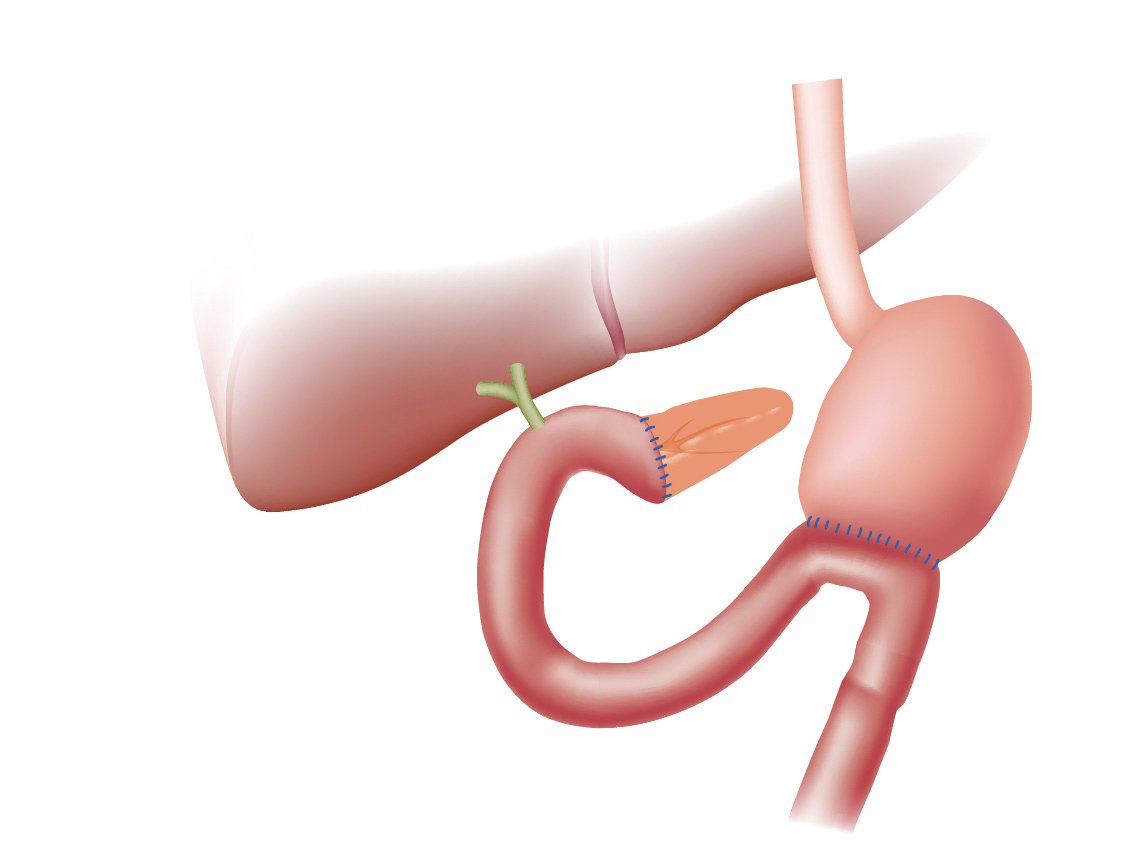

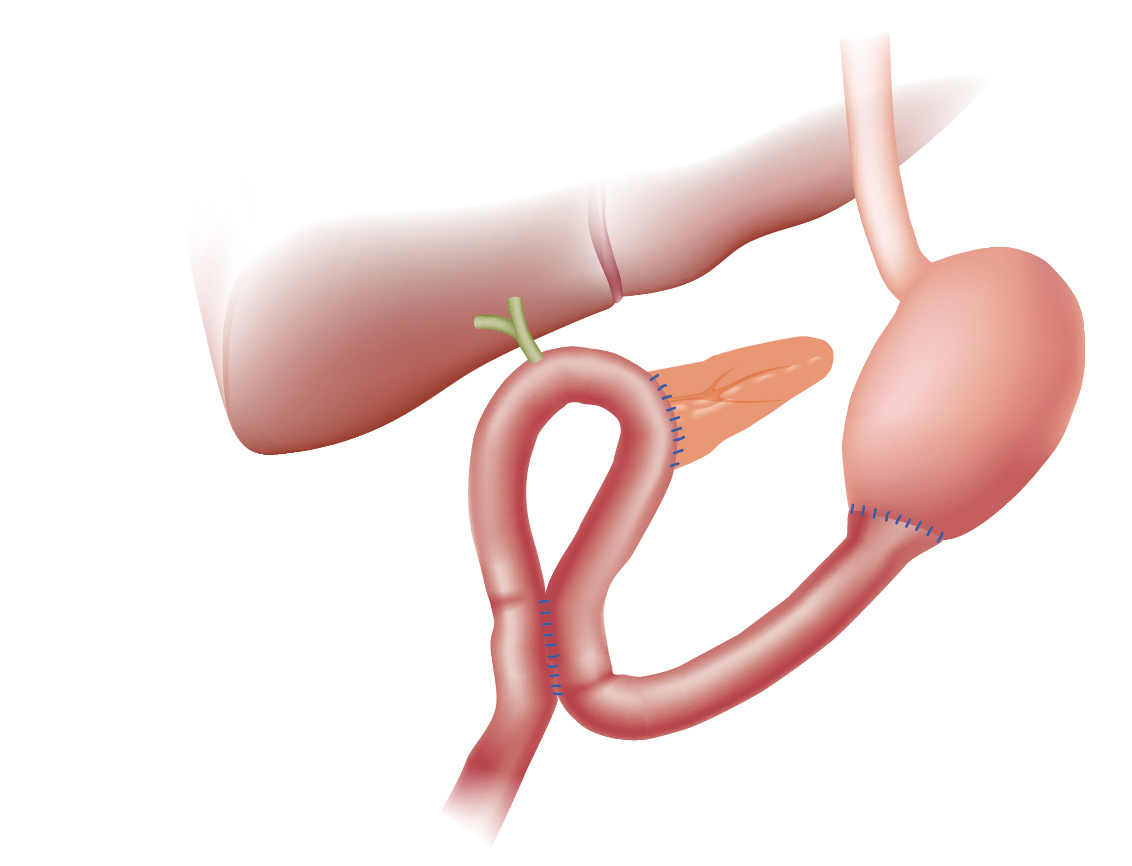

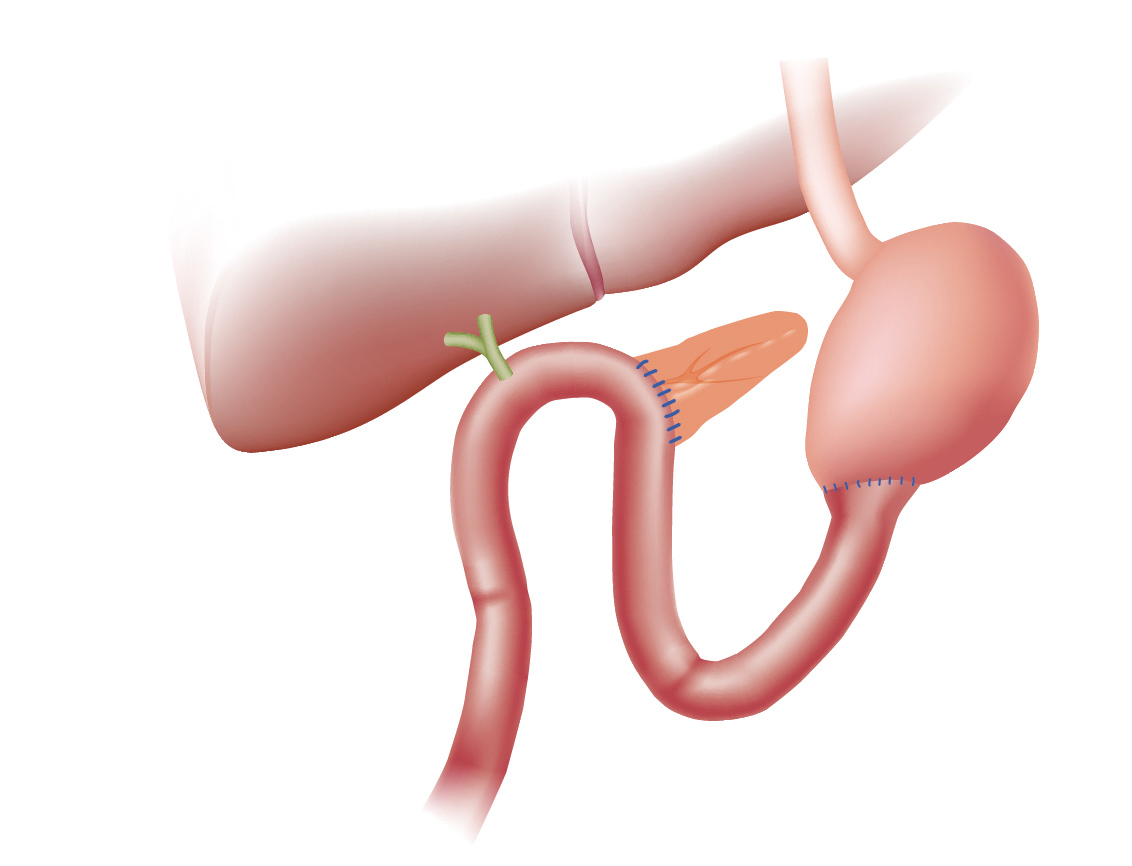

The reconstruction methods used following pancreaticoduodenectomy are classified according to order in which organs are to be reconstructed. From the oral side of the jejunum, the methods to anastomose the jejunum to the pancreas, bile duct, and stomach include PD-I (in the order of the bile duct, pancreas, and stomach) (Whipple procedure), PD-II (in the order of the pancreas, bile duct, and stomach) (Child procedure), and PD-III (in the order of the stomach, pancreas, and bile duct) (Cattell procedure, Imanaga procedure). With PD-III, there are many cases where ERCP using an ordinary side-viewing duodenoscope is possible. With PD-I and PD-II, on the other hand, there are many cases where it is difficult, making forward-viewing sSBE useful.

Illustrations of reconstruction procedures after pancreaticoduodenectomy

・Workflow and insertion tips

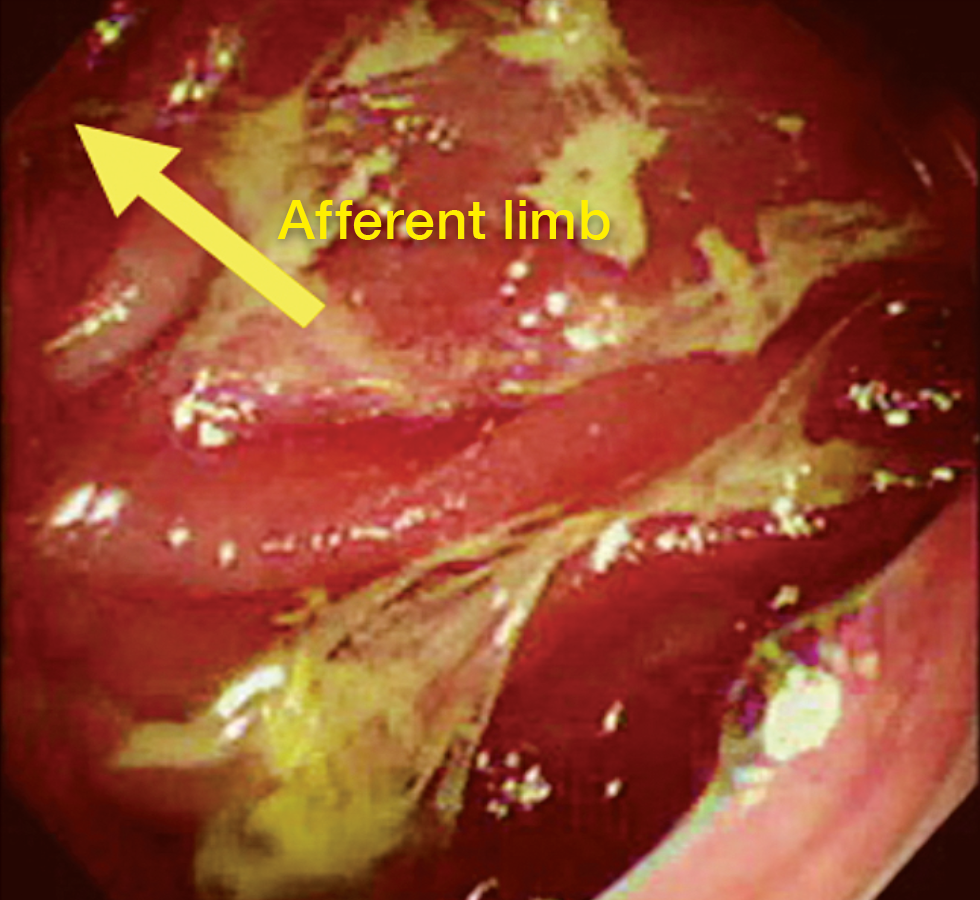

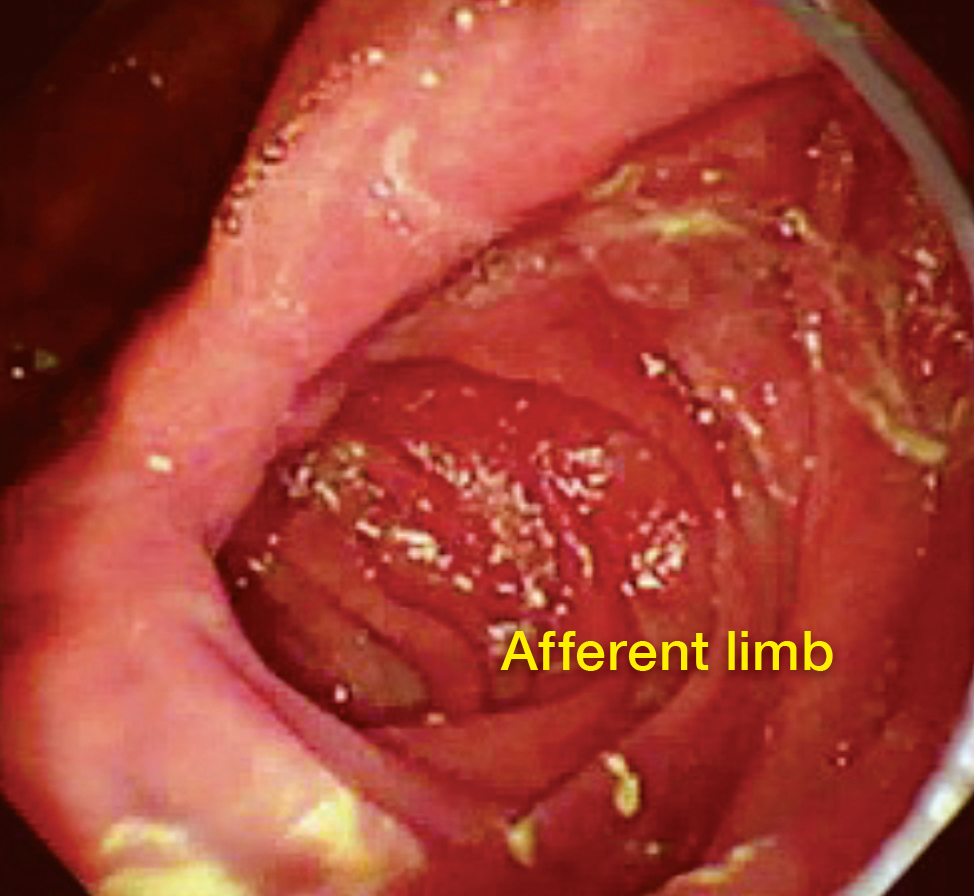

The first step in patients with a reconstruction following pancreaticoduodenectomy is to advance the endoscope to gastrojejunal anastomosis so that you can identify afferent limb and efferent limb. In most cases, the tract where it is easy to observe luminal interior and insert the endoscope is efferent limb, while the tract with the sharp angle that makes insertion difficult is afferent limb.

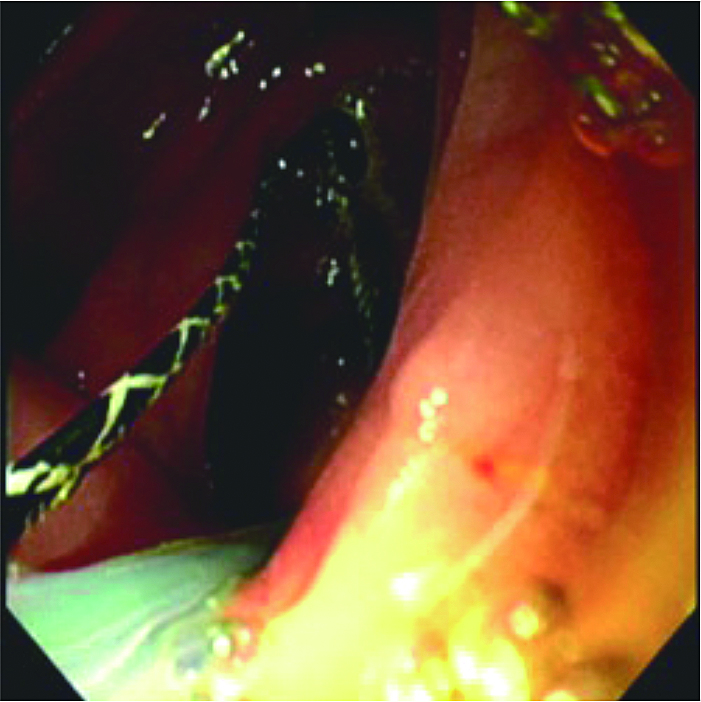

Empirically speaking, the lumen visible beyond the anastomosis on left or upper-left side is usually afferent limb (Figs. 2a, 2b).

Because the sharp angle can make it difficult to insert the endoscope using push maneuver alone, the endoscope is advanced to afferent limb using a combination of angulation and pull maneuvers. Once the endoscope has been advanced far enough, the splinting tube can be advanced. This makes insertion easier without warping the endoscope’s insertion tube. The endoscope is then advanced further while confirming its position with fluoroscopy as required. If the endoscope tip moves in the direction of pelvic cavity side rather than liver side, it is likely that the endoscope is advancing towards efferent limb. In this case, the endoscope should be pulled back to the anastomosis and inserted in the tract on the opposite side. When the endoscope is inserted in afferent limb and moved forward, pneumobilia is often found — which can be used as a reference point. In some cases, afferent limb may be long, so the splinting tube should be advanced in combination with fluoroscopy and small bowel should be shortened as required. If the endoscope becomes overly warped as it is being advanced, the most effective solution is to have an assistant perform hand pressure.

Tips on biliary cannulation

・Identification of the anastomosis

Since a gastrojejunal anastomosis is usually located in the vicinity of apex of afferent limb, it is relatively easy to identify. Pneumobilia can also help identify the anastomosis.

If it is difficult to identify an anastomosis in cases accompanied by stenosis, it is a good idea to advance the endoscope all the way to blind end and then look for unnatural tightening of folds and scars while pulling the endoscope back gradually.

・Basic approach and troubleshooting

As soon as anastomosis is identified, cannulation is performed with a catheter and guidewire in the same way as in ordinary ERCP. If stenosis is so strong that cannulation is difficult, a small-diameter catheter (PR-110Q-1, Olympus) should be used. If bile duct axis cannot be aligned by angulating the endoscope, a papillotome or a bendable catheter (SwingTip, PR-233Q, Olympus) can be used.

Case Study: Endoscopic therapy after Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Child procedure)

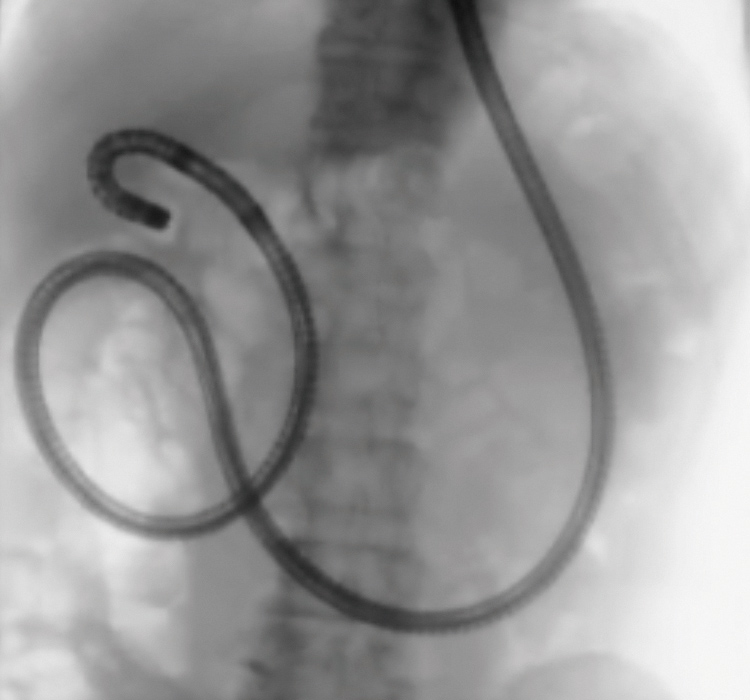

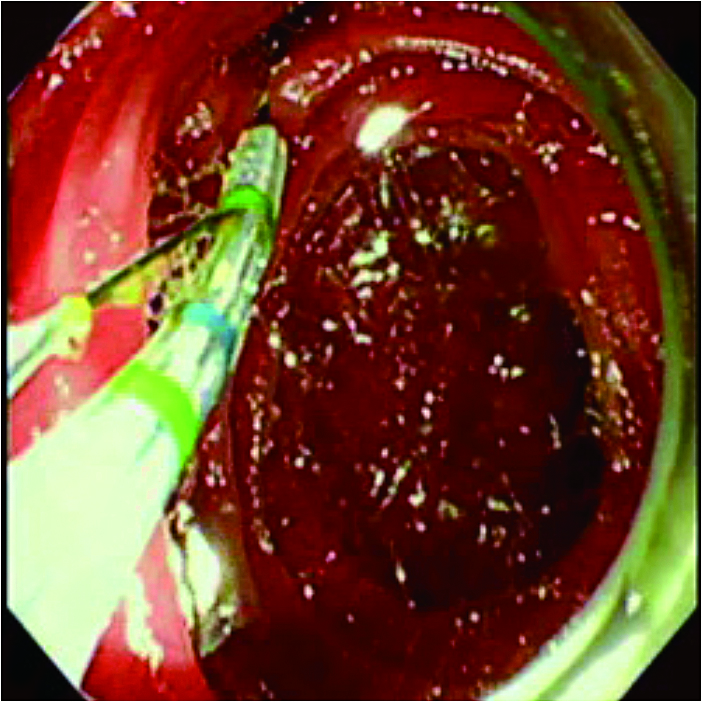

The patient was a 69-year old male. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Child procedure) was performed for an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm at another hospital. He was referred to our hospital because calculi had been found in the intrahepatic bile duct during postoperative follow-up, so we performed endoscopic treatment using SIF-H290S in order to remove the stones. Because SIF-H290S has a short working length of 1,520 mm and a large channel diameter of 3.2 mm, many endoscopic therapeutic devices used for ordinary ERCP can be used. In this case, the afferent limb was long and formed a loop midway, so we released the loop by twisting and pulling the endoscope (Figs. 3a, 3b). In addition, the afferent limb was warped downward during the endoscope insertion, so we had the assistant apply hand pressure to the lower abdomen to facilitate deeper insertion. Although we had some difficulty operating the endoscope due to strong bending of the small bowel in the vicinity of the choledochojejunal anastomosis, we were still able to reach the anastomosis thanks to the improved operability made possible by SIF-H290S’s reduced bending radius and Passive Bending capability (Fig. 3c). Then after having used a papillotome, we angulated the endoscope tip to cannulate the targeted bile duct using a wire-guided cannulation (WGC) technique for injection of a contrast medium for fluoroscopy of the bile duct. Finally, we performed lithotomy using a basket catheter (TetraCatch V, FG-V436P, Olympus) (Figs. 3d, 3e).

Preventing accidents

The most significant risk in therapeutic pancreaticobiliary endoscopy using a small balloon enteroscope is accidental damage to lumen and perforation. In consideration of patient comfort and safety, it is important never to perform forcible insertion. Because adhesion is often present in small intestine near pancreaticobiliary anastomosis especially after pancreaticoduodenectomy, neither forcible insertion nor shortening should ever be performed if any resistance is felt while operating the endoscope. It is difficult to precisely predict intestinal adhesions based on preprocedural CT evaluation; therefore, it is critical to pay close attention to what you feel while operating the endoscope, as well as to information obtained from fluoroscopy during insertion. Although this therapeutic technique has proven valuable as a minimally invasive treatment that can replace surgical treatment, it has a high degree of difficulty and should only be performed by endoscopists with extensive experience in endoscope operation who are thoroughly familiar with therapeutic pancreaticobiliary endoscopy and treatment devices.

- Content Type